When something goes wrong, it’s easy to look back and think “it was so obvious that was going to happen, the clues were all there.“

The helpful clues might have been there, but so were thousands of unhelpful clues that only separated themselves after the fact.

In Don Norman’s book “The Design of Everyday Things” he shares some thoughts on that:

Hindsight is always superior to foresight. When the accident investigation committee reviews the event that contributed to the problem, they know what actually happened, so it is easy for them to pick out which information was relevant, which was not. This is retrospective decision making. But when the incident was taking place, the people were probably overwhelmed with far too much irrelevant information and probably not a lot of relevant information.

Taking it a bit further…

Hindsight makes events seem obvious and predictable. Foresight is difficult. During an incident, there are never clear clues. Many things are happening at once: workload is high, emotions and stress levels are high. Many things that are happening will turn out to be irrelevant. Things that appear irrelevant will turn out to be critical. The accident investigators, working with hindsight, knowing what really happened, will focus on the relevant information and ignore the irrelevant. But at the time the events were happening, the operators did not have information that allowed them to distinguish one from the other.

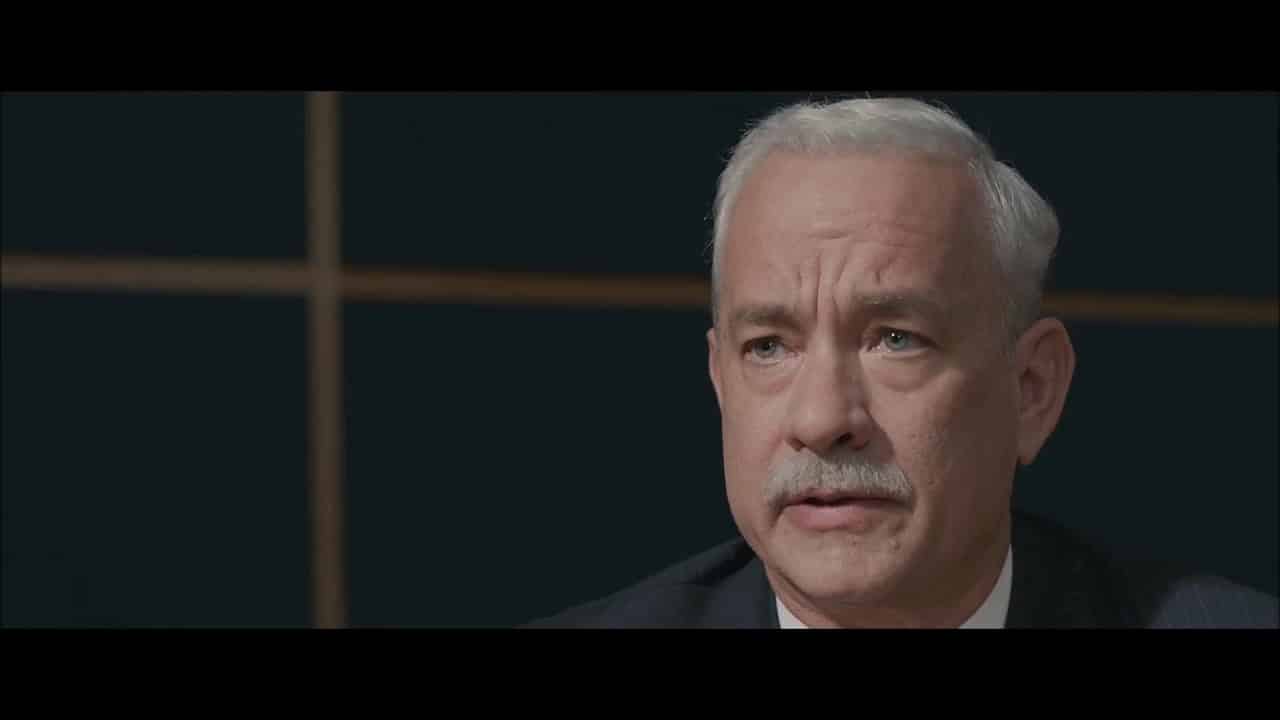

Sully

This reminds me of the events that led up to the “Miracle on the Hudson” back in 2009, where US Airways Flight 1549 lost both engines and successfully landed the plane in the Hudson River, saving everyone aboard.

While most people applauded the captain’s efforts that day, some questioned whether he could have turned back and landed at the airport. In retrospect, knowing all of the final facts, he absolutely he could have made it back to LaGuardia Airport. In real-time, though, there was no chance. From the movie “Sully”:

You can watch the remainder of that scene here.

Compound Interest

This also ties into my recent post about the compound interest of knowledge. My friend Tony connected that post (comment found here) to this quote from C.S. Lewis:

“Good and evil both increase at compound interest. That is why the little decisions you and I make every day are of such infinite importance. The smallest good act today is the capture of a strategic point from which, a few months later, you may be able to go on to victories you never dreamed of. An apparently trivial indulgence in lust or anger today is the loss of a ridge or railway line or bridgehead from which the enemy may launch an attack otherwise impossible.”

Those “little decisions” are impossible to see coming, and are almost invisible when they happen, but are crystal clear in the rearview mirror. I remember how an off-hand comment from a friend back in 1996 changed my summer plans a tiny bit, but that ultimately led to me moving to Atlanta, meeting my wife, having kids, and starting a business. That one comment wasn’t a big deal when it happened, but in hindsight it was huge.

Hindsight is superior, and can be used to learn from our mistakes, but it rarely should be used to criticize a decision made while in the midst of the chaos.